The alternative theory of electromagnetism

2nd or 3rd revised edition - 1st edition was around 2016-2017

Static magnetic field

Relativistic electromagnetism

Patrick Kawecki

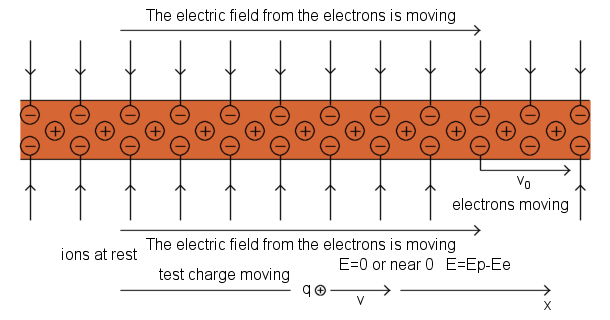

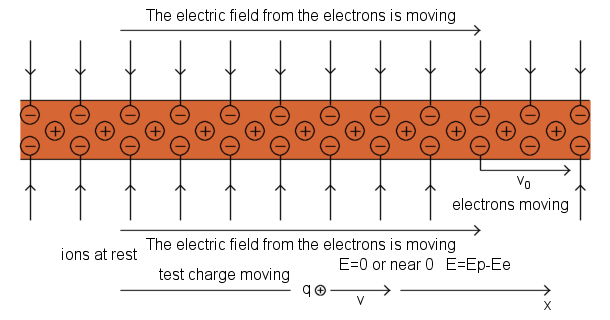

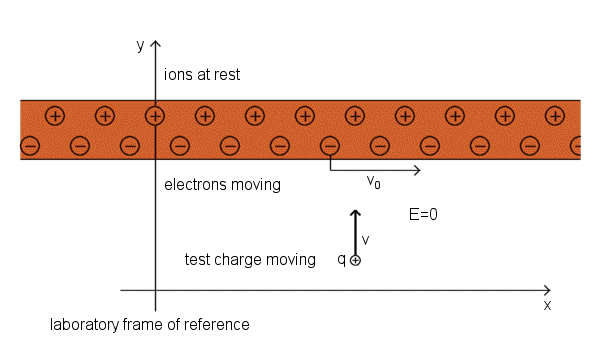

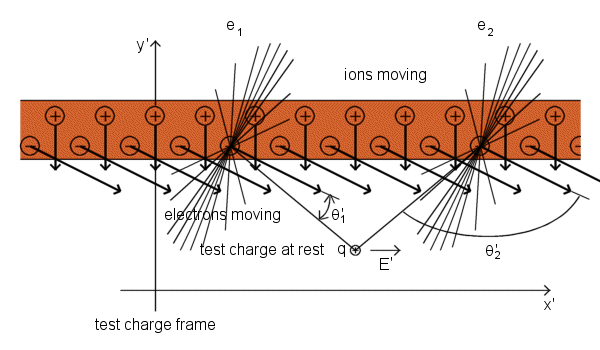

Current-Carrying Wire, positive ions and electrons are shown separated for clarity

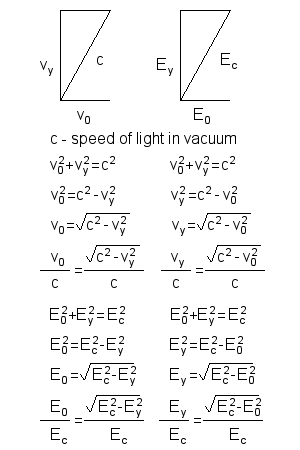

Electric field lines move together with the electrons and remain perpendicular to the conductor, but because they move sideways, the electric interaction propagates at a slight angle, thus creating a component of the electric field parallel to the conductor - this parallel component, just like the electric field of charges, decreases with increasing distance from the conductor, and this component parallel to the conductor is our magnetic field.

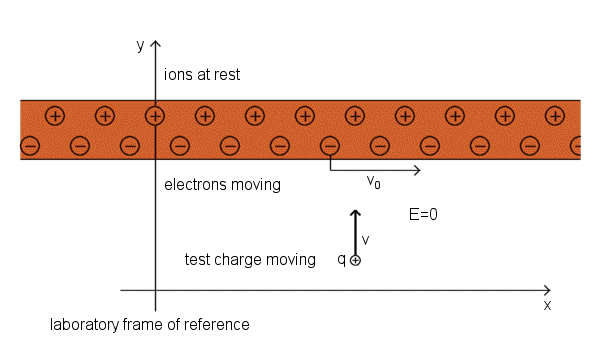

Interaction between a current-carrying wire and charge moving at right angle to the wire.

Edward M. Purcell Electricity and Magnetism, Berkeley Physics Course, Vol. 2 in SI units

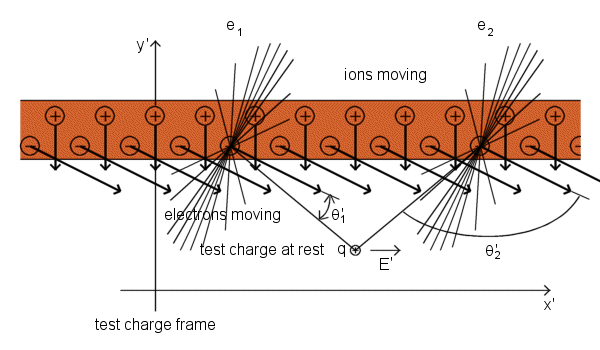

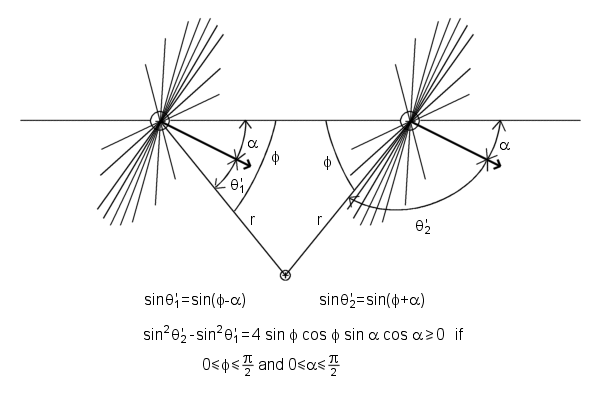

Charge moving perpendicular to the wire experiences a force parallel to the wire, perpendicular to its direction of motion. Positive ions cannot cause a horizontal field at the test charge position. The x' component of the field from

an ion on the left is exactly cancelled by the x' component of the field of a symmetrically positioned ion on the right. The effect we can see is caused by the electrons. Electrons are all moving diagonally in the test charge frame,

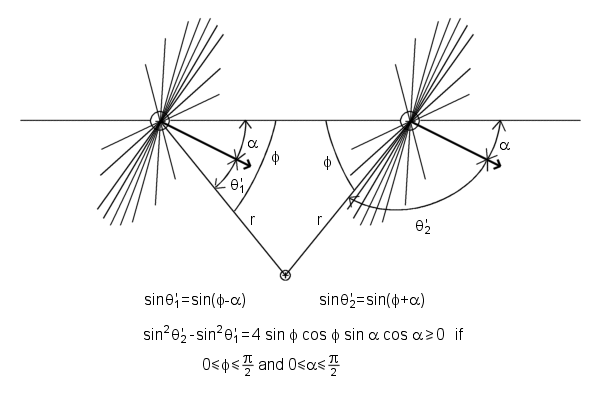

downward and toward the right. Consider the two symmetrically located electrons e1 and e2. Their electric fields, relativistically compressed in the direction of the electrons' motion, are represented by a field

lines. You can see that, although e1 and e2 are equally far away from the test charge, the field of electron e2 is stronger than the field of electron e1 at that location. That is

because the line from e2 to the test charge is more nearly perpendicular to the direction of motion of e2. In other words, the angle θ' that appears in the denominator of equation for the magnitude of the

field of electron in the frame moving relative to the electron is here different for e1 and e2, so that sin2θ'2 > sin2θ'1. That is true for

any symmetrically located pair of electrons on the line, as you can verify with the aid of picture. The electron on the right always acts stronger. Therefore, summing over all the electrons must give a resultant field E' in the

x direction. The y' component of the electrons' field is exactly cancelled by the field of the ions. That E'y is zero is guaranteed by Gauss's law, for the number of charges per unit length of wire is

the same as it was in the lab frame. The wire is uncharged in both frames. The force on the test charge, qE'x, transformed back into the lab frame is a force proportional to v in the x direction, which is

the direction of v×B if B is a vector in the z direction, pointing out of the page.

alternative, theory, electromagnetism, electromagnetic theory, magnetic theory, electricity, electric, explained, magnetism, origin, source, basics, physics, science,